You already know it’s important to get vaccinated against the flu, even though protection is neither absolute nor guaranteed. But what makes the Influenza virus such a formidable enemy?

What is a Virus?

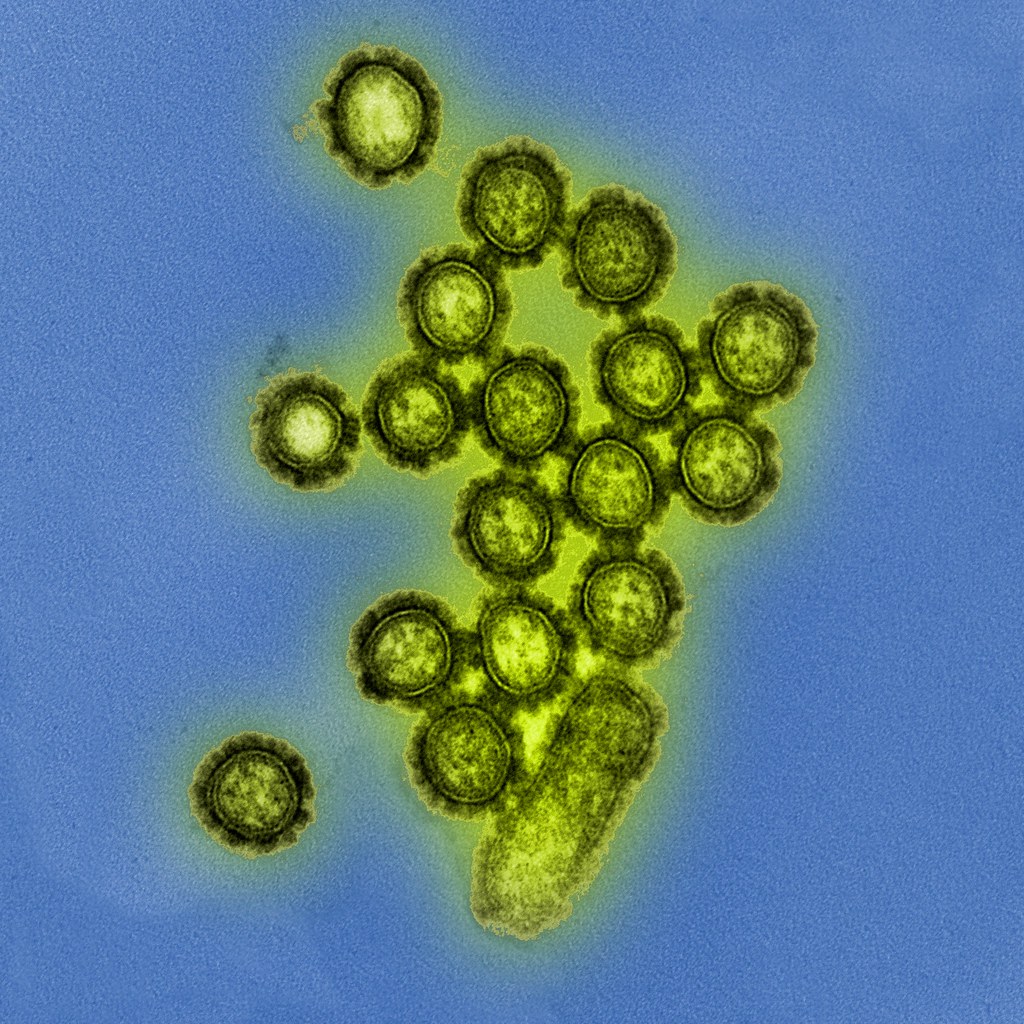

A virus is an infectious agent consisting of a nucleic acid – DNA or RNA – surrounded by a protein capsule. Once it infects a host cell, a virus replicates within it until the cell bursts. The newly released viruses then infect neighboring cells.

Our immune system protects us from viruses by detecting and removing them before they can wreck havoc. The detection of viruses depends on surface “markers” on their capsules. These identifying structures, called antigens, are recognized by antibodies and white blood cells, triggering a protective response.

Influenza the Trickster

As a result of random mutations during replication, the influenza virus frequently changes its surface antigens. This phenomenon, called antigenic drift, allows the virus to trick the immune system into thinking it’s something else. Antigenic drift is a major reason one can catch the flu more than once.

If a mutation (or their accumulation) results in a vastly different surface marker, an antigenic shift occurs. Shifts are responsible for pandemics like the swine flu.

Given the ever-changing nature of its surface antigens, it is impossible to predict exactly which strains of influenza virus are likely to circulate on any given year. The best epidemiologists can do is study the data and assign probabilities.

The Flu Vaccine

The three or four strains most likely to be prevalent are then used to produce the next season’s vaccine. But due to antigenic drift, scientists are always playing catch-up. The likelihood of an unexpected strain suddenly emerging as dominant, or different versions of expected ones circulating, is high. In either case, the result is the same: neither the temporary immunity offered by vaccines nor the more robust immunity derived from previous infections is an adequate match.

If there’s a silver lining, it’s that antigenic shift is often subtle; new antigens don’t differ significantly. Antibodies elicited by the vaccine won’t be a perfect match, but they’ll still bind to the viruses. This is how the vaccine offers partial protection and ameliorates the severity of illness even when infection occurs.

The Flu Season

Influenza infections become more prevalent in the fall and winter months. This period is called the flu season, and tends to peak around February.

Flu season occurs in colder months because the influenza virus is more stable in cold weather. Unlike cold viruses, flu viruses spread through the air, and stay airborne longer when air is cold and dry.

Even the word influenza points to the virus’s affinity for frigid weather. It is speculated to come from influenza di freddo – “influence of the cold.”

Main Photo: “H1N1 Influenza Virus Particles” by National Institutes of Health (NIH) is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0